Photographer Michael Dweck On The 10th Anniversary Of The End: Montauk, N.Y.

If you look up the word artist in the dictionary, one of the definitions reads (n) a person who produces works in any of the arts that are primarily subject to aesthetic criteria. However, an artist is much more than that. It is someone who is not only able to find beauty, but more importantly, it is someone who is daring enough to capture it, whether it be with a camera, a paintbrush, or even just words. And although artists have different styles that appeal to different audiences, some manifest their vision so beautifully, that it is almost impossible for an observer to dislike, or even ignore. Michael Dweck, the world-renowned photographer, is an artist who can do just that.

A true New Yorker (born in Brooklyn and raised in Bellmore, Long Island) Michael Dweck is no stranger to the art world. From taking pictures of Jones Beach as a child in the 1970’s to running a very successful advertising agency, to ultimately establishing himself as a world-renowned visual artist, Dweck has seen it all. And whether it be at an exhibit at the Louvre in Paris showcasing his photography or at an art installation at Art Basel displaying his famed mermaid surfboards, Dweck has been able to eloquently capture his subjects in ways that never fail to inspire his audience.

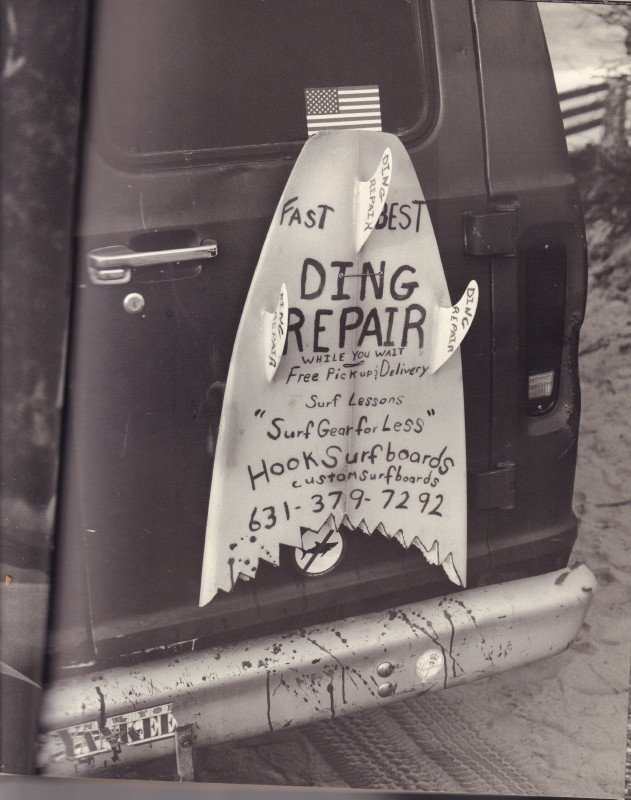

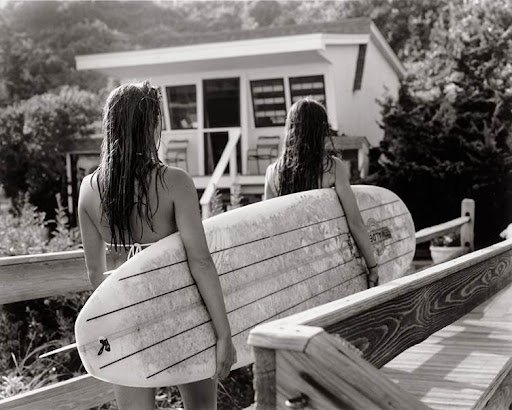

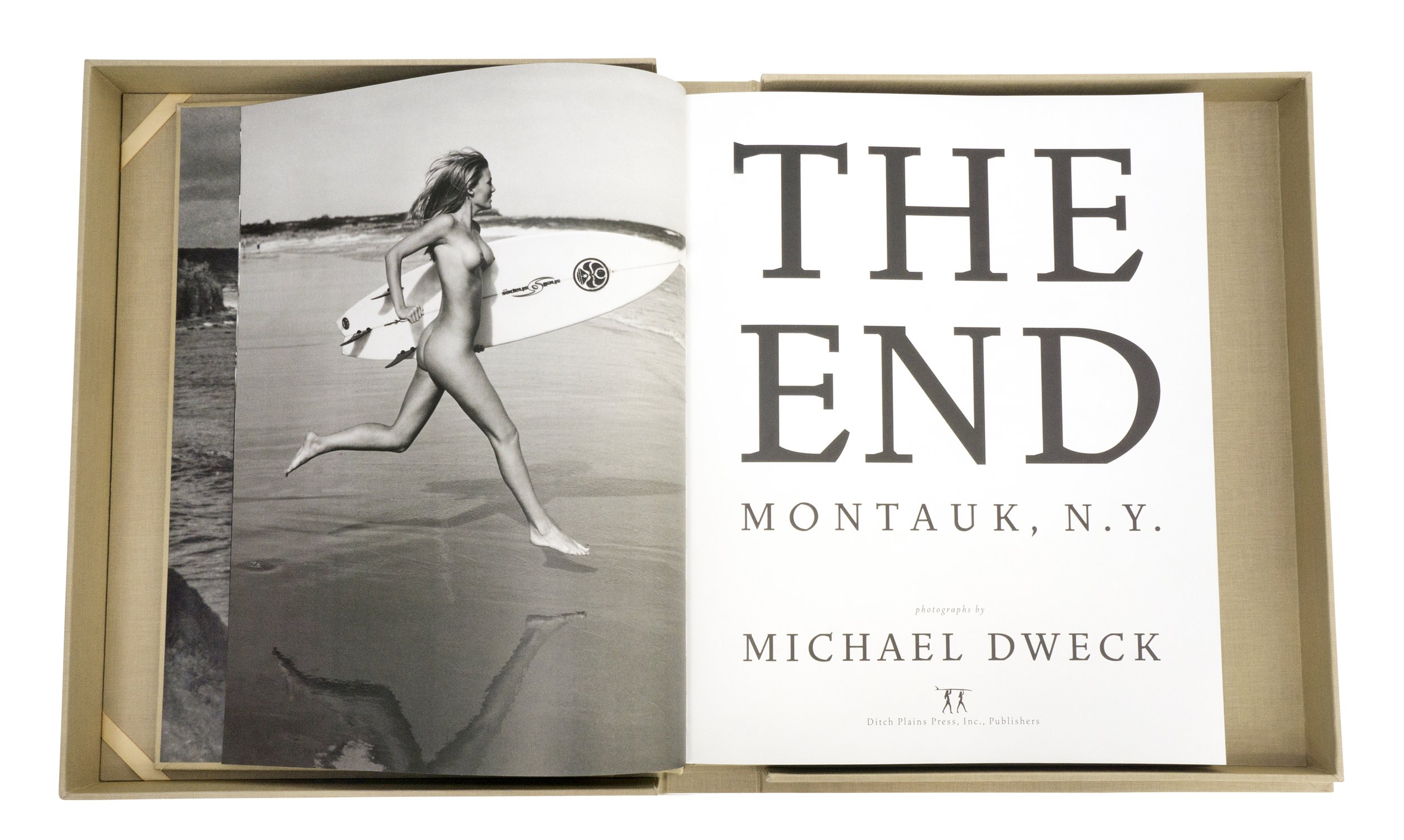

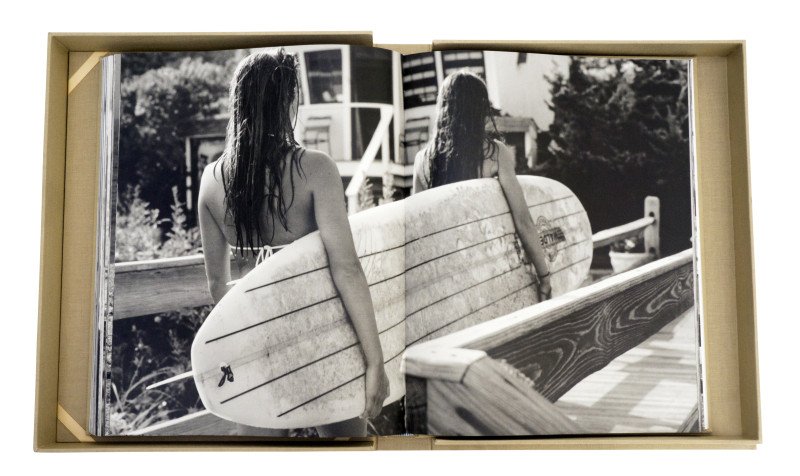

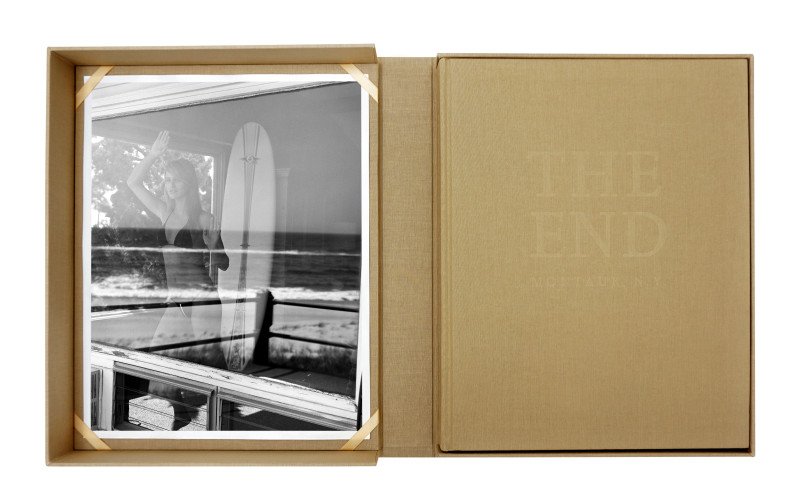

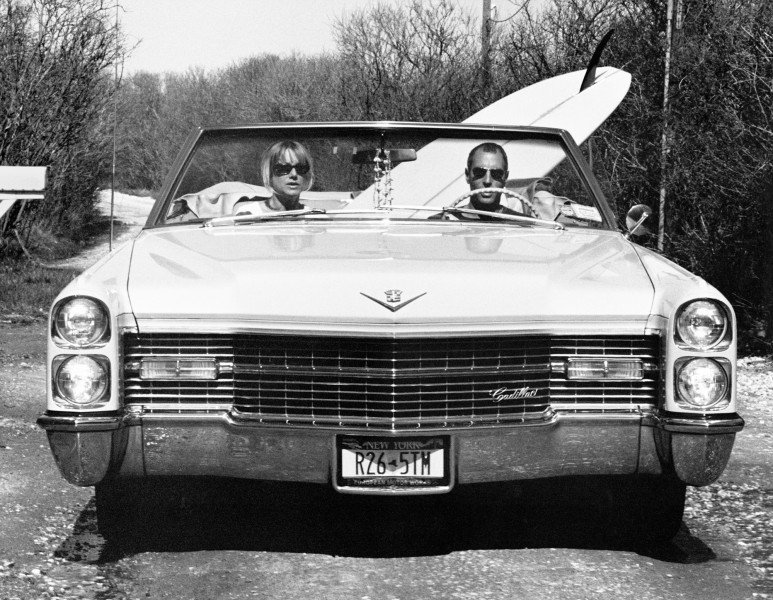

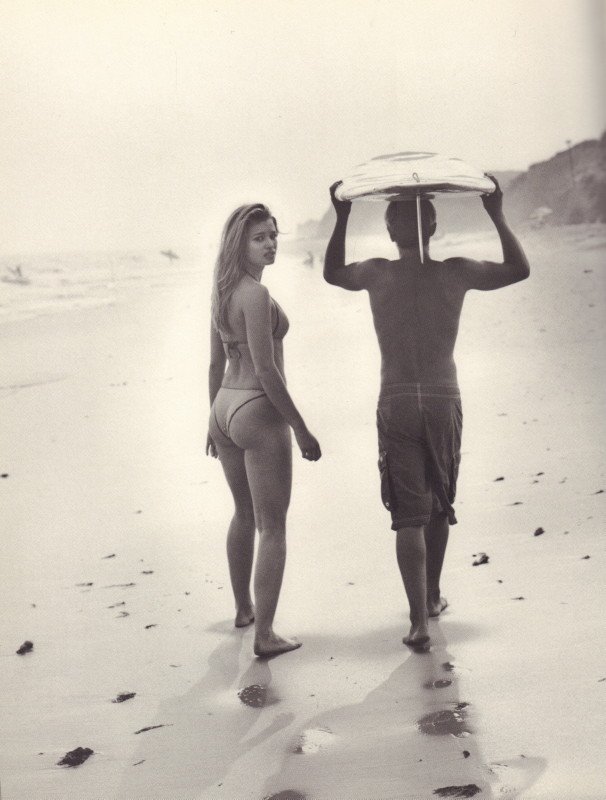

In addition to his art installations and exhibits, Michael has turned many of his artistic expeditions into photographic journals, one of which is his famed book entitled, The End: Montauk, N.Y. Intrigued and encapsulated by the pure love of surf and beach life of the community that he so often frequented, Dweck’s book is a visual representation of the inspiration that this fisherman’s town has had on his artistry and creative eye. So now, 10 years after its original publication, Dweck will release an expanded 10th anniversary art edition of The End: Montauk, N.Y., which includes original essays by both himself and renowned fellow photographer and Montauk frequenter, Peter Beard.

Printed in Italy, each copy will be signed, numbered, and packaged in a handmade, cloth-lined clamshell case, with an exclusive 11×14 silver gelatin print, also signed and numbered. Having seen it myself, I can assure you that this beautifully and meticulously constructed book, is worth every penny, for the man behind the lens is one who so passionately believes in his work – a sentiment that cannot only be seen but also felt with each turn of the page.

So, what started as a visual documentary paying homage to a place that was once one of America’s best-kept secrets, The End: Montauk, N.Y. has turned into one of the most iconic photographic works of this century. And in a time when our environment is so rapidly changing, Dweck’s book can gracefully capture the beauty of the past, but with an appreciation for the present and a thirst for the future.

Read below to see the full Q&A session with Michael Dweck:

The Tidalist: You are a true native and longtime resident of Long Island. You’ve seen it evolve and change in many ways, especially around Montauk and the areas you pay tribute to in the book. What are your thoughts on the evolution and changes that have occurred since the book’s publication in 2004?

Michael Dweck: It’s funny, because, in ways, that’s the big question I haven’t been able to answer for the last ten years. It’s hard to see something you love change, but at the same time, it’s foolish to pretend everything will stay the same. That conflict was part of the impetus for the original collection when I started conceptualizing it in 2000. I knew Montauk would change, and I wanted to capture some of the sentiment and beauty before it faded – specifically, I wanted to capture the way Montauk made me feel… And I didn’t want to be right here – ten years out from publication – being one of those sentimental, nostalgic people who whine and rant about change, you know? In that way, the collection achieves a lot of what I wanted it to – it freezes Montauk for those who want it frozen, and it lends some insights to those who don’t know what the hell their sentimental neighbors are ranting and whining about.

But I try not to deal in specifics, because I don’t think it’s necessarily an artist’s job to hold vigils (not that I don’t hold a bit of a personal candle for the East Deck and Salivar’s). I just know that I can’t really be objective, so I put the onus on my photographs to honor establishments or condemn developers… Does that make any sense?

TT: It certainly does… As a photographer, you have traveled and explored some of the most beautiful, interesting, and diverse places and locations around the world, but your love and loyalty for New York seems to always remain the same. What is it about New York, for those who may not understand, that lures you back and contributes to being your favorite place in the world?

MD: Well, I don’t think I could leave New York even if I wanted to… I grew up here. This has been my only real home, so you’re kind of adding the natural attraction that everyone feels to NY with the innate attachment that people have to the first place they’ve called home. It’s a tough spell to break.

At the same time, though, you could extrapolate my personal feelings on Montauk to the City, the State, and on and on… 2015 New York is certainly not the place where I grew up. Again, I’m not going to weep over the changes or organize a vigil – but it’s tough seeing your city loose the footholds that once nurtured artists and outsiders and the like. We’re hemorrhaging our creative class, and it’s scary to think that – if I were born today – I might be forced out to Detroit to pursue a career as a visual artist… I dunno… That’s a whole ‘nother conversation.

TT: When you first came up with the idea to publish your iconic book, The End what was your main goal, and what has been the most rewarding part of the journey?

MD: Like most of my work, The End: Montauk, N.Y. started as an attempt to build creative walls around a very particular, cloistered scene – its characters, its setting, its lifestyle, etc. – and then, from that, capture an idealized impression on that scene.

So, I didn’t want to be the documentarian who explains a foreign world, nor the insider bragging about his haunts, but rather a filmmaker, in a sense, who transports you to new environs, immerses you in a place and time and tells a story in the process. Then, when I was working on the collection, this type of narrative work wasn’t really being done in fine art – but I knew I couldn’t do justice to Montauk – both as I knew it and imagined it – without approaching it as something with a plot…

As far as the rewards of the journey – the fact that I’m here reflecting on this work ten years later kind of says it all for me… I never thought The End would go out of print in two weeks, or generate the kind of demand that it has. I especially never thought it would ever become something on this scale – a large-format, signed numbered edition with prints and all that. It’s incredible.

It’s all been incredible, really – I’ve heard from thousands of people who respond to the work, and that’s a huge reward for me. This project was all about making material something that previously had existed in my mind as equal parts memory and reverie… It’s been tremendously meaningful to see so many people respond to the story, the characters and, moreover, the place – Montauk.

The next reward will come when I get to share this with people again… we’re doing some special events in the fall, and an Art Basel event, all leading up to the release of the 10th-anniversary limited edition box set of The End. I think that’s when it will really sink in.

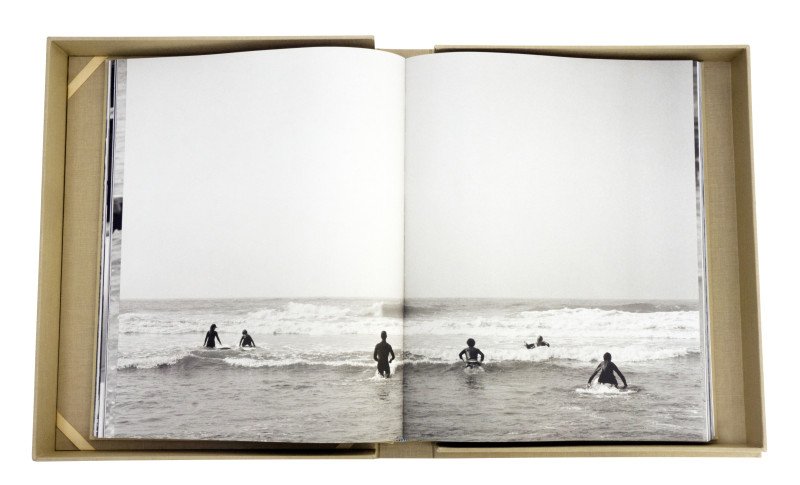

TT: Surfing is a main focus in your life and obviously in the book as well. What, in your opinion, differentiates surfing from other sports and activities? Do you think the city’s energy and dichotomy between the beach and city life make it especially different in New York?

MD: I’m not even sure if I can explain it, because it’s not even about the sport, but often what it represents – there’s escapism, balance, and a certain humility (before nature), or that need for adaptation… I don’t know many things in life that test a person – physically and spiritually – like surfing does. I mean, I’ll challenge any golfer who says his or her sport is a better metaphor…

Even as an artist, I’d be lying if I said my approach to my work hasn’t been inspired in some way by surfing. Trying to build a focused body of work – especially a narrative – is an endeavor that starts you off in some helpless, chaotic, and confusing places… I mean, you go out there with an idea, and you’re floating around, and you have to paddle and get up, or you’ll end up with a pile of shit… Maybe that’s not the best metaphor, but you get the idea. There’s not a huge margin of error in art, photography, or filmmaking, and you have to get your timing and balance down…

As far as the second question – I can’t really compare the sport in NY to anywhere else. Maybe I’m too close to it. I grew up on Long Island, and now, I can see the Hudson from my place in Manhattan, so it’s just part of who I am. I grew up surfing and sailing and fishing. I’m most comfortable when I can stumble to the shore. I can’t imagine growing up on the coast and not feeling that way… I’d venture that that’s the same anywhere.

TT: Although Montauk and the East End has changed as time has progressed, there is undoubtedly still that sense of allure and untouched beauty about it. What are some of the things you still love most about this beach community?

MD: We’re talking about one of those places that just feels different, you know? You don’t have to tell a first-timer that they’re going somewhere special, because they can just get out of the car and feel it. And that’s still there. It’s something intangible – and for that matter ineffable. You can’t explain it, and you can’t erase it. That’s my Montauk: That’s what developers can’t destroy, and tourists can’t tread over… It’s a feeling that you get at Ditch Plains, or talking to a fisherman before a storm, or just staring out at the sea at sunrise. Something about the community, the natural beauty, the lifestyle… See, I can’t even finish my sentences… that’s the feeling.

And that’s the reason for the charitable component of the new book release. We’re giving a portion of the proceeds from each book to protect the ocean and those fragile shores, because of that feeling. If we lose that, we lose so much… How do you rebuild a feeling… something ineffable?

TT: What’s up next for you in your career… We know you are working on your first feature film. Can you tell us a bit more about it?

MD: Sure… It’s a full-length doc following two years at The Riverhead Raceway – another endangered Long Island haunt that’s close to my heart. I did a 360-look at all aspects of the place – from the individuals who drive the beat-up old stock cars, to the commercial threats that will eventually shutter the track (which is Long Island’s last). I grew up going to the track, so it’s a bit of a personal piece, but there’s also some of the same metaphor you might see in Montauk, or my work in Habana Libre… I’m making a case for endangered identity and underrepresented art… you know, as the shadows of strip malls creep into the frame. I like to describe it as “a David vs. Goliath story, only if David were a tow truck driver and Goliath were a Walmart…”

I’m really excited about it. I did a whole series of abstract pieces that tie in with the film, so it’s kind of a real mixed-media project too.

TT: If you could describe your perfect day, what would it consist of?

MD: Art would have to be one component of it… Probably what I call a “click day,” that one day during a project when all the ideas and hopes you have for something kind of click together, and you realize, “Hey, this thing might actually work!” (And I’m sure that happens in a surfer’s career, as much as it does an artist’s…) That’s what keeps so many of us going – when everything falls into place and you feel invincible. Maybe that breakthrough on a big project, followed by drinks and dinner with friends and family?

Is that lame? Nevermind – Let’s go on a trip to Mars, and dinner with Godard.

TT: You ran a very successful ad agency before you became a successful full-time photographer. What are some of the things that you are most appreciative of now that you can focus on your main passion?

MD: It was always about art. I was just lucky enough to realize – or re-realize – that when I did. I had some trepidation of course, but at the same time, I knew about Warhol and Irving Penn (both art directors in advertising), so I knew it wasn’t an impossible jump to make. It’s all about sensibilities and instincts. As an artist, you just get to treat those with more sincerity and let them come through as something raw and visceral.

Now, I mean, I appreciate it all. Being able, as I said before, to make real-world versions of ideas – and moreover to have those ideas reach people, and reach minds… That’s the beauty of art – a narrative about a small community of the East End may reach people in a way that an editorial on over-development can’t… I get to work in a medium that provokes and teaches in inexplicable ways. Like Whitman says (another Long Island guy, actually) “I and mine do not convince by arguments, similes, rhymes; We convince by our presence.”

That, to me, is art. The fact that I can be part of that… wow.

TT: Who have been some of the biggest professional and personal inspirations in your life?

MD: Again, without getting too specific, I’ll say, anyone (or thing) that’s resilient despite being repressed, adventurous despite being mortal, and creative despite being engineered solely to survive. That could be surfers in Montauk, or poets in Franco’s Spain… There’s no shortage of inspiration if you pay attention.

TT: Is there anywhere else in the world you would live?

MD: Again, I’ve always been interested in the way geography affects culture, and, moreover, how it creates exclusive groups. So I guess I have a running list with that criteria in mind: Africa, Asia, South America, Australia, Europe (again), and, why not, Antarctica.

A special thank you to Michael Dweck for not only taking the time to speak with me about his work but for his constant artistic inspiration on life and for his ability and courage to capture the ethereal beauty that surrounds us.

Photo Credits: Michael Dweck Photography